In any natural history of the human species the invention of language would stand out as the preeminent trait.

It is impossible to imagine life without it. Language enables us to communicate, to facilitate learning, to plan, to develop a “theory of mind” and the tools of thought.

So tightly is it woven into the human experience that it’s scarcely given a second thought. We open our mouths and speak. We open a book and read.

We use it with such natural, innate ease it’s not hard to overlook the fact that language is a completely artificial construct consisting of sounds and symbols that we process effortlessly. Words, being the linguistic objects they are, are proxies for the things they represent. They are increasing in number exponentially and stored in the vast lexicon of the human experience. In that lexicon, names have a special role.

We name things to create order and make sense of our world and everything in it – to understand something as itself and also its relation to other things. We name countries, states, cities, street, mountains, rivers, planets, craters on the moon, distant stars, pets, boats. And we name all living things.

The classification of living things is one of the more arcane and scholarly branches of naming. It is one of the most overlooked, and one of the most beautiful.

According to Jessica Leigh Hester in her truly fascinating article in Atlas Obscura, The beautiful complexity of naming every living thing, scientists go about naming much in the same way any other namer would, regardless of what they are naming. In fact, her article would serve as an excellent primer for any namer.

Like all namers, scientists have their own jargon and naming protocols. In their world they use “binomial nomenclature”, a naming system based on two words. Blatella germanica, for instance, is a cockroach; Homo sapiens are, as you know, humans.

It wasn’t always so neat and tidy. In 1758 a Swedish naturalist, Carl Linnaeus, was putting the finishing touches to the 10th edition of Systema Naturae, his encyclopedic work of taxonomy, when his attention fell on the European honeybee, known at the time in scientific circles as abdomine fusco, pedibus. Accurately descriptive as it goes – it means “furry bee, grayish thorax – it was a bit of a mouthful

Renaming the honeybee

He decided a more practical approach to naming was needed – the binomial nomenclature. The honeybee was renamed apis mellifera (honey bearing bee), a name it still goes by today in entymological circles.

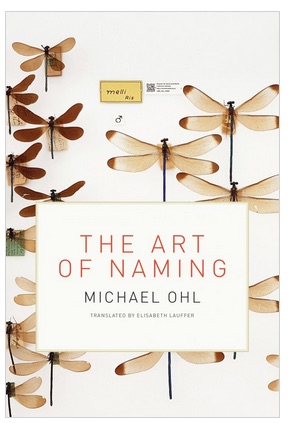

The scientist’s approach to naming is reassuringly structured, as you would expect. But then Ms. Hester concludes her article with a quotation which must go down as one of the most lyrical and transcendent testaments ever made to a namer’s art. It is taken from German biologist Michael Ohl’s book, The Art of Naming. He writes:

“Part of the majesty and magic of a name is how it gives the reader or listener a firm, solid foundation from which to transport herself to a place she’s never been. Names nudge open portals to new parts of the world or the long-receded past as though they were secret incantations…mental images of prehistoric landscapes take shape at the sound of their names, and we feel we are among the initiated, the entrusted, the knowing.”

The beauty of language and the art and science of naming captured in a single paragraph.