When change overwhelms a technology company, the impact can be sudden, shocking and irreversible.

The quote above is by former RIM co-CEO Jim Balsillie* when sales of the Blackberry were in meltdown.

Much the sentiment was echoed by Stephen Elop, the last CEO of Nokia before it was acquired by Microsoft, when he said with a touch of self-pity and more than a tinge of denial, “We didn’t do anything wrong, but somehow we lost.”

Both comments should together serve as a cautionary tale of our time for every product-based technology company. One minute you’re king of the world, the next you are struggling to understand what happened.

The pace of change in the technology industry can be breathtaking. The demise of Yahoo has been glacial in comparison, but even its inevitability did not mitigate the shock of its sale this year to Verizon and its end as an independent company.

How what was once a $125 billion behemoth squandered its pre-eminent brand position as the king of the Internet and was sold for chump change is a story that remains to be told. Watch out for the book in 2017.

There was another news headline of 2016 that caught the eye, one not quite as dramatic as that of Yahoo, but more richly instructive as a tale of a storied technology brand in decline.

* * *

News came in January that Xerox is splitting itself into two to “realize shareholder value” six years after a major acquisition that was intended to finally propel the company into a brave new future beyond copiers. Shareholders lost patience. The plan had failed.

News came in January that Xerox is splitting itself into two to “realize shareholder value” six years after a major acquisition that was intended to finally propel the company into a brave new future beyond copiers. Shareholders lost patience. The plan had failed.

What happened?

Difficult market conditions and aggressive competition certainly play their part, but great companies take such exigencies in their stride. At the heart of Xerox’s predicament is the tale of a celebrated global brand trapped in its own shadow.

The Kodak parallel

In many ways, the fate of Xerox is bound up with that of close relative Kodak. Both were founded in the same city and in the same industry at roughly the same time, both met with spectacular business success, both brands became virtually synonymous with the product that bore their name and both struggled to renew themselves beyond their legacy business.

By the early 20th century, Rochester, NY had become the center of the U.S. optics and photographic industries.

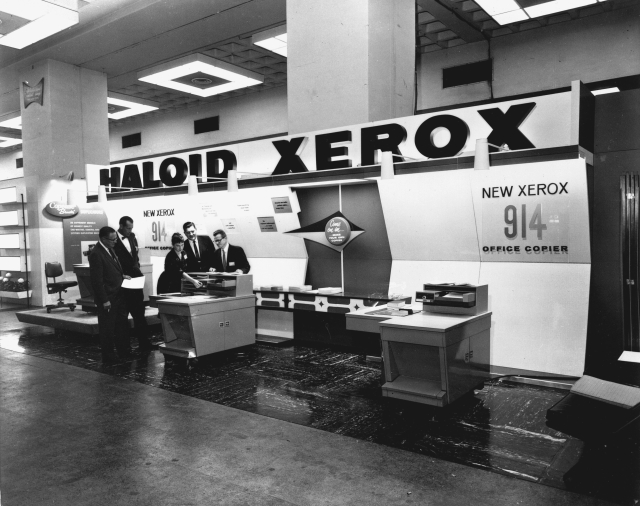

Bausch & Lomb, the lens manufacturer, was founded there in 1853. Kodak started life as the Eastman Dry Plate Company in 1881. Xerox was incorporated across town as the Haloid Photographic Company, a manufacturer photographic paper and equipment, in 1906.

Kodak dominated the city. The Kodak Tower, a 19 story skyscraper completed in 1914 was Rochester’s tallest building for more than 50 years until it was overshadowed by another edifice in the late 1960s. That building was the Xerox Square Tower.

George Eastman’s influence spread far beyond Rochester. Kodak camera and film business model put photography into the hands of ordinary American’s at a time of rising prosperity and unsurpassed personal mobility. Between 1908 and 1927, Henry Ford had put some 15 million Model T cars on the road and people took road trips and took photographs with their Kodaks to memorialize the journey.

For all his invention, Eastman’s real genius lay in branding and marketing.

He metaphorically burned his device into popular consciousness with a non-technical, unique, easy-to-remember name. Legend has it that he and his mother devised the name Kodak with an anagram set. He later said that there were three principal concepts he used in creating the name: it should be short, one cannot mispronounce it, and it could not resemble anything or be associated with anything but Kodak.

The creation of Xerox

Eastman’s branding lesson could not have been lost on Rochester neighbor Joseph Wilson. When he took over Haloid (named after a chemical salt) from his father in 1936 the photographic paper market was dwindling and he urgently needed to reinvent the business. Physicist Chester Carlson provided the answer with a process for printing images using an electrically charged drum and dry powder “toner”.

Wilson signed an agreement with Carlson to commercialize the process and decided it needed a brand name. Following Eastman’s naming precepts for Kodak, Wilson and Carlson came up with Xerox, a name that closely mirrors Kodak in structure and concept*.

The success of the first dry plain paper photocopier (Xerox 914) was so huge that the company changes its name to Haloid Xerox in 1958 and then Xerox Corporation in 1961.

Both Xerox and Kodak prospered mightily in mid-century and both brands became household names, synonyms for the products that bore their name – Kodak for film, Xerox for copiers. And in that immutable truth is the seed of what was to be a profound problem for both companies.

As late as 1976, Kodak commanded 90% of film sales and 85% of camera sales in the U.S. But the digital revolution was just around the corner and in spite of its innovation and invention of digital photography, Kodak remained captive to a legacy business that threw off enormous amounts of money and the brand that symbolized it.

In a declining market the company slowly and inexorably slid towards oblivion as it proved incapable of change. Kodak filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection in January, 2012 and has re-emerged as a much smaller technology company focused on imaging.

The business lesson

Xerox met with its own struggles. Asian rivals ate into the copier market in the 1990s and in the early 2000s Xerox had a brush with bankruptcy.

By 2009, the company had been nursed back to financial health and new CEO Ursula Burns took a brave gamble to avoid the same ruinous fate as Kodak. The Xerox story was going to be different.

The company unveiled a “transformational deal” the biggest acquisition in its 103-year history and joined the wave of hardware makers expanding into services with a $5.6 billion deal to acquire Affiliated Computer Services (ACS).

“By combining Xerox’s strengths in document technology with ACS’s expertise in managing and automating work processes, we’re creating a new class of solution provider,” said Ursula Burns. “A game-changer for Xerox, acquiring ACS helps us expand our business and benefit from stronger revenue and earnings growth.”

Unfortunately, things did not work out that way.

The stock remained roughly flat while the market capitalization of the company was down and in January this year, nearly six years after the acquisition, Xerox bowed to investor pressure and announced it was reversing course and splitting in two, effectively dismantling the acquisition of ACS.

The brand lesson

A new company named Conduent (see Name Origins) will be responsible for business process outsourcing on its launch in early 2017. The remaining document, copier and printer business will retain the Xerox name.

Xerox is back to square one, same brand, basically the same business but with a different CEO. Ursula Burns will be replaced by Jeff Jacobson, who is currently president of Xerox Technology. Ms. Burns will become Chairman.

Could the outcome have been any different? Possibly, with a different brand strategy.

Hindsight is 20/20 but a certain amount of informed foresight is essential when it comes to brand positioning, brand strategy and business transformation.

Xerox took a brave gamble to avoid the devastation that befell Kodak but there was a brand lesson embedded in the debacle – that of the paradoxical weakness at the heart of powerful brands and widespread suspension of disbelief that often surrounds them.

Xerox was looking for radical change. The ACS acquisition was positioned as “transformational” deal. At any time of business transformation the question has to be asked: Is the brand capable of making the transformational journey along with the business, or will it be an anchor that holds us back?

For Xerox, a brand born in the early part of the last century, a brand so attached to a product that it has become a generic verb for the action of copying, it is was a massively critical question – is Xerox the brand to go forward with; does it have the elasticity and attribute power to credibly represent a 21st century solutions company; do we have the data to make a decision?

Whether or not Xerox asked the questions and had the answers, the company placed its transformational bet on the Xerox brand and commissioned advertising agency Y&R to develop and superbly execute a multi-million dollar campaign designed to “disrupt legacy perceptions” of the brand with the rubric Ready For Real Business.

The problem here is that disruption of legacy perceptions is a long game to play.

IBM has achieved it, but very carefully and over decades. It takes time, investment, patience and strategic clarity. When time is short and transformation is the objective, the best way to disrupt brand perceptions, if they need disrupting, is to change the name.

While the idea may have been sacrilege for a brand like Xerox it had the wormhole of an opportunity to come out of the gate wholly reinvented with a new brand – call it Conduent for argument’s sake – a brand with a powerful, future focused vision for exploiting that $500 billion market to handle the back-office operations for businesses and governments, and with no legacy perceptions to change.

Xerox could have been folded into Conduent as an operating division and, as CEO, Ms. Burns would have had time to consider what to do with the Xerox brand from a more objective and considered vantage point, perhaps spinning it off eventually as a pure-play hardware company to appease shareholders, if necessary, or selling the brand to the Chinese. And she would still be in the CEO’s chair.

In fact, it’s not so radical a strategy.

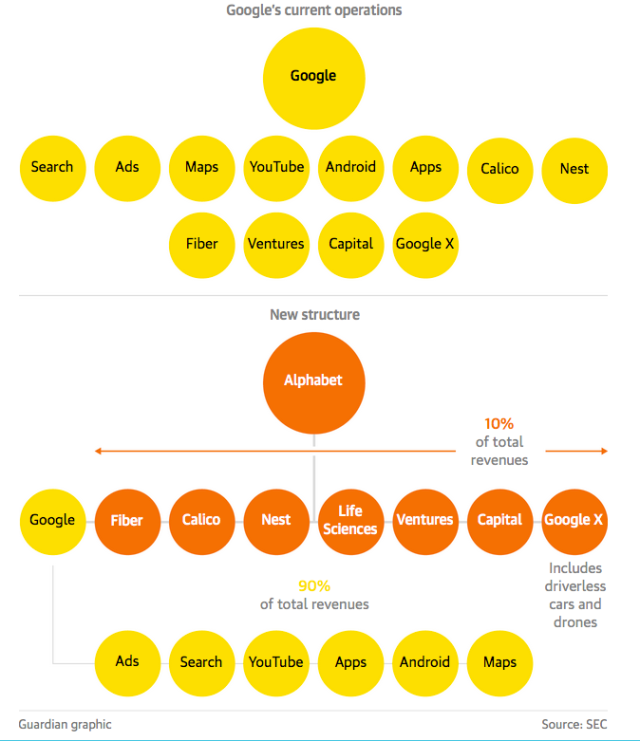

Several energy utilities (Exelon, NextEra Energy, Sempra Energy) have restructured themselves in this way to surround a legacy business and grow beyond it. And, if a sexier example is needed, it’s exactly what Google did last year when it created Alphabet. Even though Google is still immensely profitable, what the company will be in 10 years, and what the search engine’s role will be in it, is anyone’s guess, but Alphabet has future-proofed its options.

Where does Xerox go from here?

At the time of the ACS acquisition an unnamed top ACS executive told the Dallas News, perhaps self-servingly, that “Xerox was dead in the water. It had no future. With ACS, it has a future, but it has to make something of it.”

Xerox no longer has ACS. Is it dead in the water?

Not yet. The last chapter of Xerox has yet to be written, and maybe the story will end in triumph, but the slow unraveling of a once great technology company is surely nearing its denouement.

Whatever its fate, Xerox has to be all about the Xerox brand and what it can be, not what it should be. The task is to build relevance and deepen the Xerox brand with key market segments with a clear roadmap based on data.

Its survival depends on it, and hopefully the CEO won’t have to say anything like, “We didn’t do anything wrong, but somehow we lost.”

Sources.

*From LOSING THE SIGNAL: The Untold Story Behind the Extraordinary Rise and Spectacular Fall of BlackBerry. Copyright © 2015 by Jacquie McNish and Sean Silcoff.

**The Xerox name is based on xerography – meaning ‘dry writing’ from Greek (xeros) – “dry” and (graphia) – “writing”].

As a follow-up story, you might check out the NOKIA brand phone story.

Who has the license to market a new “NOKIA” phone? Will there be one and when introduced?

If you guessed Microsoft, you’d be incorrect.

Good summary Alan. I was the head of the Xerox account at Interbrand from 2005 to 2010, and when we started the rebranding process in 2005, a move away from the Xerox name was considered (under one CEO) but was not timely. But then when ACS was acquired in 2008 (under another CEO), the recommendation was to embrace the brand evolution but not in a disruptive manner (that is, just kill the Xerox name), but in a way not too dissimilar to the IBM brand transition. It is too long (and client-confidential) to explain what went on and how the transition was to be organize, but that recommended ‘best’ course of action was well-crafted and in my opinion extremely workable. Unfortunately, it did not see the light of day.