There was a saying where I came from about unfortunate people who are easily confused or taken in. “Graham can’t tell his arse from his elbow”, we’d say.

Americans have a pithier expression: “Wade can’t tell shit from Shinola.” The alliterative ‘sh…’ sound here adds an important degree of subtle memorability and sibilant symmetry.

Until recently I had no idea what Shinola was, but whatever it was I was instinctively sure I could distinguish it from shit.

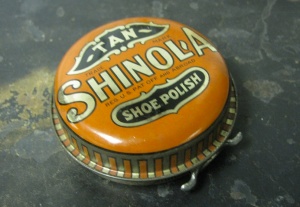

Shinola, as it turns out, was an American shoe polish brand. Wikipedia reliably informs me that it was introduced in 1907 by Shinola-Bixby Corporation of Rochester, NY.

The -ola suffix for product names was all the fashion at the time thanks to the popularity of the Pianola, a player piano that possibly derived its name from the violin-viola relationship. In 1906 the Victor Talking Machine Company launched the Victrola gramophone. Galvin Manufacturing later introduced the Motorola car radio, a ‘Victrola’ for your motor, and the whole crapola naming trend ran its course soon after.

Shinola (add shine to ‘ola’) polished its last boot in 1960 when the company went out of business but its name now lives on as something more than a euphemism for something you step in.

Shinola has been reborn as a luxury brand.

Yes indeed. You are now urged to think of Shinola in the same way you think of Mont Blanc with its expensive pens and other luxury ‘lifestyle’ accessories you don’t really need.

The company behind Shinola, Bedrock Brands, was started by a founder of the Fossil brand of watches, Tom Kartsotis. Last year, Crain’s Detroit Business reported that Mr. Kartsotis commissioned a study in which people were asked if they preferred pens made in China that cost $5, the United States at $10 or Detroit at $15, and when offered the Detroit option, they chose it regardless of the higher price.

And so a luxury brand was born, trading on the manufacturing prowess of a city that was once known as Motown, the Motor City. And its name is Shinola?

Shinola opened the doors of its flagship store in New York’s Tribeca neighborhood in July. The Shinola product line consists of an unlikely paring of watches, bicycles and leather goods, many of which are made in Detroit, or at least assembled in Detroit. Yes, you can buy Shinola shoe polish at$15 a can and, if the impulse takes you, there’s a “Rare American Flag” going for $15,000 in the ‘curated’ section its website. Add it to your cart.

All-in-all, Shinola leaves you with an odd, empty feeling. The product set has no brand focus. The faux authenticity of its story, straddling a “storied American brand, and a storied American city”, is bizarrely schizophrenic. Shinola is by no stretch a ‘storied’ brand. What stories are told about Shinola apart from its association with shit? It is all off-the-mark marketing cliche and hype.

Detroit, on the other hand, could be a winning idea. Clint Eastwood’s raw, gritty Super Bowl commercial for Chrysler in 2012 “Halftime in America” hit exactly the right note. It was an uplifting tribute to a great American city and a great brand.

The sentiment behind the Shinola brand tries to capture that same spirit but fumbles it. What have Detroit and Shinola got to do with each other?

Is the brand Detroit, is it Shinola, or is it something you just want to wipe off your shoes?