Fans of Frank Capra’s film It’s a Wonderful Life will recall with distaste the conniving banker Mr. Potter, the richest and meanest man in Bedford Falls.

George Bailey, played by James Stewart, falls afoul of Potter and is driven to the edge of suicide on Christmas Eve, saved only by the intervention of Clarence, his guardian angel.

Potter, or Henry F. Potter to give him his full fictitious name, occupies slot #6 on the American Film Institute‘s list of the 50 Greatest Villains in American film history. People just don’t like him.

This scene, where George Bailey confronts Potter, could be a post-2008 parable of our time.

So it was with some ambivalence I read that Nationstar, one of the biggest nonbank mortgage servicers in the US and whose name is associated with mortgage crisis, distressed loans and foreclosures, is creating a new brand with the name “Mr. Cooper”.

Mr. Potter? Mr. Cooper? Mortgages? Haven’t I seen this movie before?

According to the Dallas Morning News, executives at Nationstar have spent more than a year and roughly $5 million on the branding overhaul. The hope is that consumers will see the new name as an extension of a new company ethos, “personable, customer-focused and easily navigable online.”

The rebranding comes as the company, which grew into a niche borne of the massive rise in distressed mortgages, adapts to a shifting industry. As the housing market recovers Nationstar needs new ways to grow, especially after a difficult year that saw the departure of several senior executives and a 60 percent fall in the stock price.

President and CEO Jay Bray said making existing customers happy is a top priority. So building a recognizable digital-savvy brand that will attract customers for life is a logical step forward.

“Mr. Cooper is meant to be that advocate that person that’s going to connect with the customers to deliver best — better experience and to be an advocate for them day in and day out,” Jay Bray said on an earnings call.

Nationstar will be well shut of a tired, generic corporate name that is lost in the Landstar, Ameristar, Coinstar morass of sameness and, it’s true, personal names have worked well in the financial services industry in which service should be the operative word.

The names of Messrs. Wells and Fargo have served the bank well since 1852, and J.P. Morgan, Edward Jones and Charles Schwab built financial empires on their personal credibility. Charles Schwab’s “Talk to Chuck” campaign in 2005 was a great way of capitalizing on the personal integrity and acumen of an individual, also signaling there was a real person on the end of the phone to talk to for advice, if not Chuck himself.

But, like Mr. Potter of Bedford Falls, Mr. Cooper is a fiction.

We are invited to relate to a man who doesn’t exist. Who is he? What does he stand for? What does he look like? Maybe the company will invent a Colonel Sanders-type spokesperson to give the brand flesh and blood substance. Even the Colonel was real, though. Given the artificial, digital nature of the brand, Max Headroom might be a better avatar (remember him?).

The world is changing around Nationstar and its ilk and it presents a seminal opportunity for them to reinvent what it means to be a mortgage company in the age of digital brands and heightened customer expectation. It had to do something.

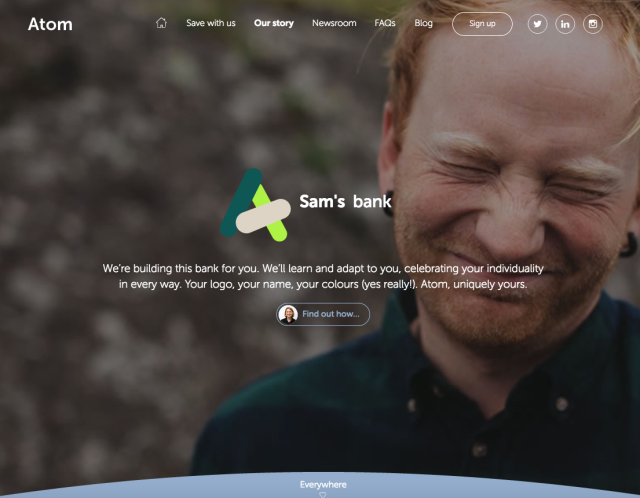

The financial services industry is alive with the sound of molds cracking and breaking. Atom Bank of the UK, for example, is building a “customer obsessed” bank brand that customers can personalize. “We were building a bank for ‘you’ (the customer) and not ‘us’ (the bank).”

Mr. Cooper feels lamely traditional and superficial in comparison. It has the hallmarks of a campaign developed by a new age ad agency. And all ad campaigns are, by their nature, transient.

The intention for the brand is not entirely clear. News has leaked out in dribs and drabs. It could part of an Allstate/Esurance strategy allowing Nationstar to hedge its bets for a while.

Whatever the intention, Mr. Cooper needs more than a “digital-savvy brand”. He needs to be given life.

Less than.

Less than.