I know, it’s been done to death. But I think it’s time to call BS on Alphabet.

The most remarkable thing about the announcement of Google’s restructuring was not the news itself but the rapturous praise that was heaped upon it. The branding community was quite giddy with excitement.

“Without a doubt the biggest rebrand in the 21st century.”

“One of the most incredible pieces of corporate brand communication I can remember.”

“A brilliant branding move.”

“A strategy at the opposite of what is typically recommended by consultants or advisors.”

The outpouring of adulation gave me pause for thought… had I missed something?

As a business story, Google’s creation of Alphabet, a holding company, is remarkable, not so much for what it is but for what it will make possible; as a branding story, it’s really old hat.

There is nothing in the creation of Alphabet that hasn’t been done many times before and equally as well by many other companies in the cause of business reconstruction and renewal.

At its most mundane, Google has turned itself into an unfashionable conglomerate. It’s a familiar tale, one told by such unglamorous conglomerates as ITW, Manitowoc and Textron. And it’s hard to forget the disastrous attempt by UAL Corp to bind together Hertz, Westin and Sheraton Hotels under a holding company called Allegis. This is a story I’d recommend as further reading for all brand strategists. If Alphabet is the branding road less traveled then Allegis is the reason why.

More worthy exemplars of the genre are to be found among the energy companies such as Constellation, NextEra Energy, Exelon. They grew exponentially beyond their regulated core utility origins by creating a holding company, à la Alphabet, so they could offer enhanced services and products in the competitive energy market, satisfying both shareholders and regulators.

The energy giant Exelon, for example, has its origins in two very humble regional utilities – PECO (Pennsylvania Electric Company), and Commonwealth Edison, which are now operating divisions of Exelon – just as Google will become an operating division of Alphabet.

For some reason we accept Amazon in all its sprawling vastness as it attempts to become the world’s retailer, even though it makes most of its money from its web services business, AWS. Google had become impossible to define. To most people, Google is a search engine; as a business, it is much more. And there, in that dynamic, is the tension that created Alphabet.

Google had grown into an opaque, messy hotchpotch of businesses, some speculative, such as driverless cars and life extension technology, and all financed by the phenomenon of Google itself, the financial nuclear reactor.

Branding Google is like trying to brand an explosion. What the new structure provides is maximum flexibility together with investor transparency, discipline and financial accountability as the company makes big bets on the future.

Google’s founders, Messrs. Brin and Page, have handed over the reins of Google to Sundar Pichai who, by all accounts, will do a good steady job. For them, Google is done. The new more enticing future is spelled out by Alphabet, which, as a name, is about exciting as cold rice pudding.

No mind, they have spun a nice story around it and, as a holding company, it will work just fine. It has no other role to play other than that of a name for a legal entity that places the big bets. What’s interesting is what will happen underneath Alphabet in the operating divisions.

Is this the branding story of the century? No, far from it. But it does provide a glimpse into the future intent of one of the world’s great companies.

The truly brave thing about the creation of Alphabet is in its invocation of what economist Joseph Schumpeter called creative destruction, ‘the essential fact about capitalism’. It is the spirit of Schumpeter that will push the company far beyond its origins and the Google brand.

I can’t help thinking such an approach might have saved two other iconic American brands that found it impossible to escape the gravitational pull of their brand’s heritage and an addiction to the cash they threw off.

Kodak missed its chance several times to evolve beyond the failing Kodak brand and determine its own future as a business. It met its inevitable end in one form of creative destruction, Chapter 11, to be reborn as something else entirely.

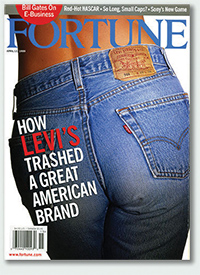

And then there is always Levis: as it seeks salvation with cheerleader CEOs who endlessly try to revive a commoditized brand by dressing from head to foot in the product, it keeps coming back to the same product conundrum of heritage versus innovation as it continues on the long, remorseless slide towards business oblivion.