In the annals of corporate branding the Allegis affair must go down as the granddaddy of all rebranding debacles.

The story is told and retold as the classic disaster, a cautionary tale of what happens when a corporate naming exercise goes badly wrong.

Why — what did go wrong? Is Allegis really that bad a name?

In truth, the fuss had little to do with the wretched name itself. There are more egregious examples of the genre that have served their corporate purpose successfully and much less controversially – Accenture, Agilent, Novartis and Verizon to mention a few. And Allegis lives on quite happily these days as a name in various corporate guises, here, here and here, for example.

The disaster, as is often the case where corporate name changes are concerned, was a compound of corporate politics, investor impatience and union unrest. Like Gettysburg, Allegis was transformed through a complexity of circumstances from an innocuous name to a proxy for a battlefield.

The Allegis story starts in 1979 when Richard J. Ferris became chief executive of UAL Inc., the parent company of United Airlines.

A vigorous proponent of airline deregulation, Ferris saw an opportunity to shake up the stodgy industry and create a new kind of company. By putting together the airline with rental cars and hotel services under one umbrella, Ferris argued that large savings could be realized and more customers could be attracted through “synergy”, a word that had new and sexy currency in the corporate world at the time.

He spoke with messianic zeal of his visionary concept of a one-stop fly-drive-sleep behemoth that would take care of the major needs of travelers. With extraordinary prescience for the time he foresaw a future in which travel agent around the world perch in front of computer screens making reservations for his airline, his hotels, and his rental cars completely seamlessly.

In a two year span Ferris spent $2.3 billion in pursuit of his vision, acquiring Hertz Car Rental, Westin and Hilton International hotel chains. In February 1987 he changed the name of UAL Inc. to Allegis Corp. to reflect the broadened scope of his travel enterprise.

In a two year span Ferris spent $2.3 billion in pursuit of his vision, acquiring Hertz Car Rental, Westin and Hilton International hotel chains. In February 1987 he changed the name of UAL Inc. to Allegis Corp. to reflect the broadened scope of his travel enterprise.

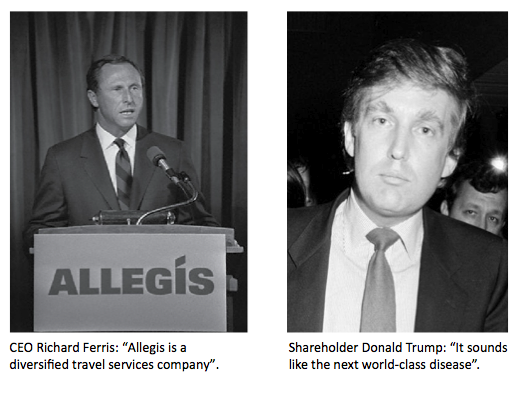

“We are a travel company, not just a transportation company”, he said. “The name change clearly identifies us as the only corporation that can offer travelers door-to-door service.”

Lippincott and Margulies, the firm that came up with the name, said Allegis “conveys the central corporate mission of service and guardianship … through its relation to the word allegiant, meaning loyal or faithful, and aegis, meaning protection and sponsorship.”

Ferris’s grand vision now had a name, and his many opponents on Wall Street had the weapon they needed. Investors were growing restless. The huge cost of putting the strategy in place became a drag on Allegis’s earnings and the stock price sank below the break-up value of the company. A disgruntled pilots union put together a bid to buy the company. Allegis was in play.

Investor discontent came into keen focus around the name change. Security analysts and institutional investors stared even harder at Ferris and his operation, which they thought was grossly undervalued. Shareholder Donald Trump, even then never lost for a pithy remark, said Allegis sounded like ”the next world-class disease.” It was merciless and unrelenting. The outfit ought to be called Egregious Corp., burbled the Wall Street wits.

Investor discontent came into keen focus around the name change. Security analysts and institutional investors stared even harder at Ferris and his operation, which they thought was grossly undervalued. Shareholder Donald Trump, even then never lost for a pithy remark, said Allegis sounded like ”the next world-class disease.” It was merciless and unrelenting. The outfit ought to be called Egregious Corp., burbled the Wall Street wits.

It was all over by the following June, less than four months after the name change. Unnerved by the ridicule, Allegis directors finally bowed to pressure from dissident shareholders who threatened a proxy fight to replace the board. They forced Ferris to resign, symbolically changed the name back to UAL, and began to dismember the company.

Ferris’s arrogance had won him few friends on Wall Street along the way. But even his harshest critics conceded that his big-picture strategy might have been workable some day. They just were not willing to give Allegis the time it needed.

The power of a name to make abstract concepts real and focus emotion and Allegis’s ready accommodation to ridicule made it a lightening rod for dissident shareholders and unions. The naming of Allegis was the beginning of the end for Ferris.

Donald Trump acknowledged as much when told the New York Times how the name had affected him:

“The name change made me more militant as an investor and more willing to speak out against management, because I thought it was so wrong,” he said. ”And I think it had an important psychological role. It brought out even more anger at management and made a lot of people say they had finally had it.”

”A name change can be an incredibly powerful thing,” said naming expert S. B. Master. ”What you’ve been saying in annual reports and speeches suddenly becomes real when you change the name. Ferris’s idea finally got through.”

Joel Portugal, a principal at Anspach Grossman Portugal, perceptively put his finger on the real long-term damage: ”For the rest of my life, I expect to hear clients joke about Allegis,” he said at the time. ”They’ll say, ‘don’t give me an Allegis,’ or ‘don’t make an Allegis out of me.’ And beneath the joking there will be real fear.”

Fear there is. Allegis became a radioactive name and the fallout seeped into corporate boardrooms of America. It is there still. CEOs have a real fear of what they think of as ‘phony, made-up names’. Like Allegis.

Karl Marx said history repeats itself, first as tragedy, second as farce. If Allegis was the tragedy, then Consignia was the farce to prove his point.

Next: The savaging of Consignia and how it could have been avoided.

Pingback: A seasonal recipe for a naming disaster «

Pingback: What’s in a name? The Juliet syndrome «

Pingback: You say Allegis, and I say Allegion |

Read this about the name Allegis

Pingback: The ABC of creative destruction |